The cultural practice of harvesting woodland plants and herbs for medicinal purposes along the Cape Fear River Basin is a risky proposition for tribal communities like the Cape Fear Band of the Skarure Woccon tribe — especially in the years since GenX, a class of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, started to be released into the river.

Centuries before Chemours began producing GenX chemicals at its Fayetteville Works facility, the Skarure Woccon, also known as Cape Fear Indians, sustained themselves by hunting, fishing and harvesting native plants in the basin.

Modern fish advisories and health studies have caused many tribal community members to alter their relationship with the land. But cultural practices are hard to abandon; some still hunt, fish and collect herbs to supplement their diets — even though for seven years, there’s been an increasing awareness of PFAS lurking in the river, soils and air.

“The Cypress tree and the Longleaf Pine are medicinal [plants] and a food source for us, and they are affected by the water,” said Jane Jacob (Eagleheart), a member of the Tuscarora tribe (Skaroreh Katenuaka Nation) of Bertie County, a part of the Skarure Woccon tribe, in a 2023 interview. “You can drink pine leaf tea and Cypress tea. They have so many health benefits, and they taste yummy as well.”

Given Cape Fear Indians’ belief in the healing power of plants, some are welcoming a recent study by Swedish researchers that finds aquatic plants can remove PFAS from water and store the compounds in their roots and shoots.

A closer look

The study, published in the Journal of Environmental Management, found that plants with high biomass, such as Carex rostrata, a type of sedge grass, can store PFAS chemicals without any yet known adverse effects to the plant.

There are roughly 15,000 to 20,000 unique per- and polyfluorinated substances in the environment, according to experts. PFAS are manufactured and used for their slippery and heat-resistant properties and are present in multiple products, such as some cosmetics and apparel, microwave popcorn wrappers, tooth floss, upholstery, carpeting and cookware.

The two most extensively produced and studied families of compounds, PFOA and PFOS, have had new manufacturing and use phased out in the U.S., but because they don’t break down easily, they can continue accumulating in the environment and in the human body. That’s one reason that the substances have been dubbed “forever chemicals."

GenX is a type of PFAS used in Teflon production. It was manufactured by Chemours at its Fayetteville Works facility in Bladen County for decades before the discovery of PFAS in the Cape Fear and surrounding areas.

In 2017, a team of researchers headed by N.C. State University epidemiologist Jane Hoppin launched the GenX Exposure Study, which revealed that some people in the Cape Fear River Basin have PFAS in their blood.

There is evidence that exposure to PFAS can lead to adverse health effects, such as weaker antibody responses against infections in adults and children, elevated cholesterol levels, decreased fetal and infant growth, and kidney cancer in adults, among other problems.

What was learned

The Swedish researchers collected PFAS-contaminated water from a freshwater lake near a military airfield in the southeastern part of that country. The source of that PFAS contamination is firefighting foam used during training exercises, according to the study. A collection of native plants wetland plants were used in the experiment.

The research involved placing a variety of plants, such as Carex rostrata, also known as bottle or beaked sedge, into a solution containing diluted PFAS-contaminated water, according to the study.

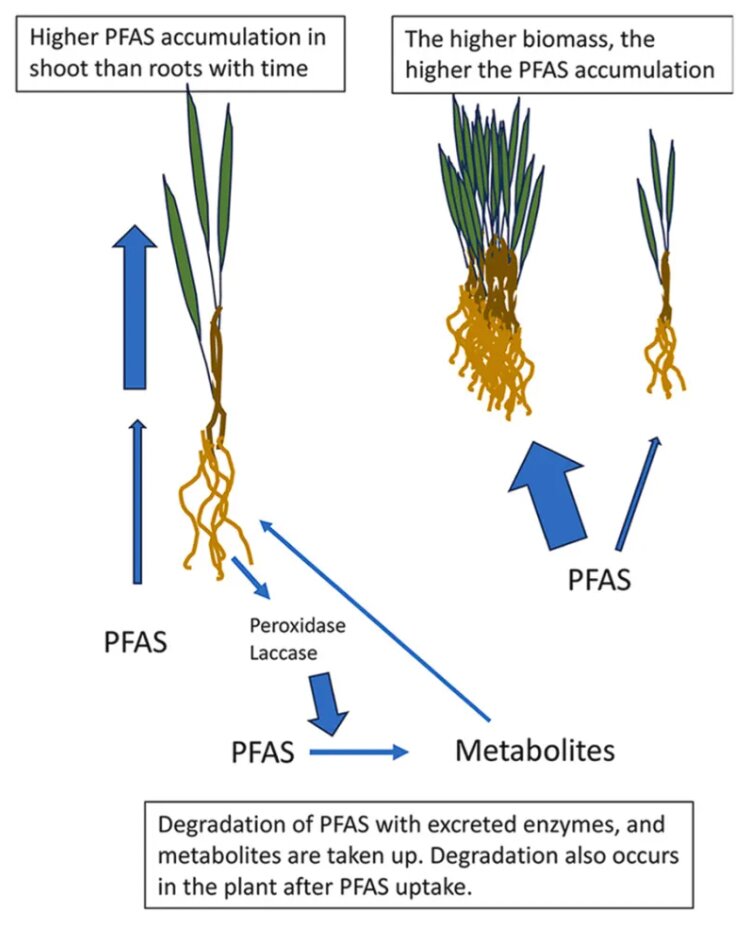

The researchers hoped to determine how well the plants soaked up PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS, from contaminated water. They wanted to look at a variety of wetland plants, evaluate the relationship between biomass and the level of PFAS removal and determine whether plant enzymes played a role in “removal and degradation of PFAS,” the study states.

According to the researchers, after plants were submerged in the solution, the study showed “varying ability of several wetland species to purify water contaminated with PFAS.” Furthermore, the study revealed that more PFAS accumulation occurs in the shoots than roots over time; plants with higher biomass absorbed more PFAS than plants with less; and enzymes play a role in PFAS degradation by converting the contaminants into metabolites.

One lingering question acknowledged in the study that will require further research is whether plants can effectively absorb PFAS in their roots and shoots in flowing water bodies, such as rivers and streams.

‘Floating wetlands’

As a result of the study, the researchers conclude “that wetland plants can be used to purify water contaminated with PFAS. Since the roots of emergent plants take up PFAS, such plants can be mounted on wetland rafts to form so-called ‘floating wetlands.’”

Could this idea work in the Cape Fear River Basin?

Jud Kenworthy, a coastal marine scientist based in Beaufort, North Carolina, was intrigued by the study.

“The ideas in the paper — especially towards the end when [the researchers] were discussing and making recommendations about these floating plant masses as a mechanism — I think, conceptually, in principle, is an interesting idea,” Kenworthy said. “I’m not aware of anybody doing that with any kind of chemical bio-filtration systems here in the U.S., let alone in Cape Fear.”

However, Kenworthy also points out issues to resolve for this research to prove effective outside of the lab’s controlled environment.

One question he has is how long can emergent plants, such as sedge grass, thrive outside of the sediment they grow in and receive nutrients from if they were part of a floating raft of plants, which he likens to “hydroponic cultivation.”

Kenworthy and Jacob are concerned that floating islands of plants that contain PFAS in their roots and shoots will affect wildlife that may seek out the floating plant islands as a food and habitat source, which could spread contamination far beyond the remediation site.

And then there’s the question of what to do with the plants once they’ve absorbed the PFAS. Sending them to the landfill or burning them could further exacerbate the problem.

While the study has limitations, Jacob believes it offers an important lesson: “The Creator gave us everything that we need on this earth to fix any [problems] that we run into.”